It took less than one week of Trump’s second presidency for the world to notice that the new conservative is fashionably subversive, aesthetically pretentious, calculatedly provocative—and young.

Last week, New York Magazine ran a cover story about the “confident and casually cruel Trumpers” with the headline “The cruel kids’ table.” What’s in are decadent house parties, martini lunches, and miniskirts. As one observer put it, “Carnage becomes carrion, not merely waste but ballast for new possibilities (including cocktails with names like American Carnage and the Second Term at Capitol Hill’s new cafe “Butterworth’s”). Conservatism suddenly has the raunch and radical edginess of self-expression of the 1960s or even the prosperous 1920s.

Liberals have viewed themselves as an elite who should guide the masses toward social salvation. As their influence slackened since the turn of the century, the liberal style became more ironic—temporarily upstaged by the joy-boosting Kamala Harris. Given the chaos and absurdity at hand, some liberals feel that events demand “a new form of sincerity”: constant irony can lock in emotional detachment, inspiring the quip that “irony is the song of the prisoner who’s come to love their cage.”

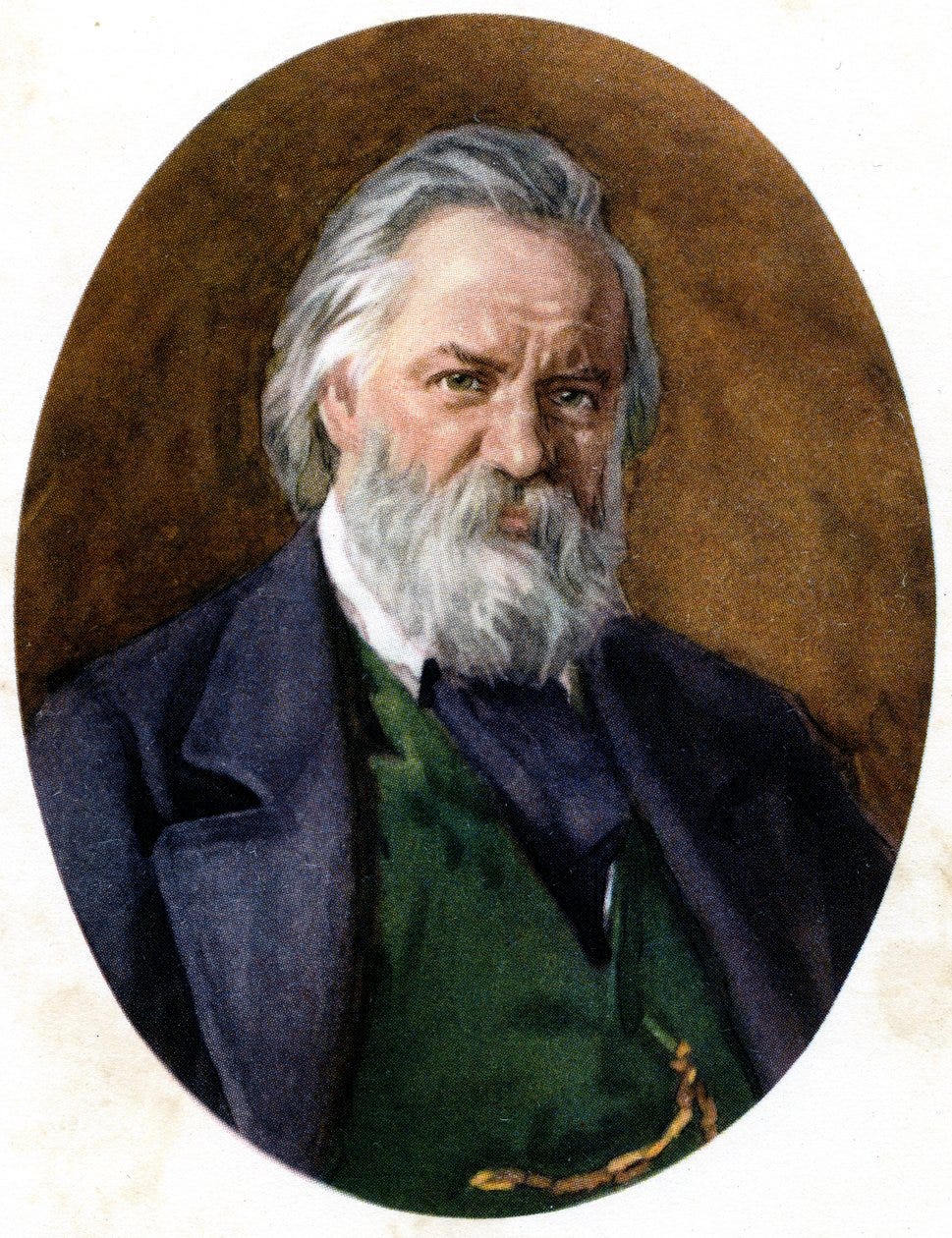

A thinker who knew such circumstances firsthand, in a time otherwise far removed from our own, bears remembrance. Alexander Herzen was a 19th-century Russian writer and revolutionary. Satire leavens the depth of his conviction, and his sincerity is pithy. Only some of his remarks:

“The public conscience is so debased in Russia that people enjoy their chains as if they were ornaments.” “The nobility has perfected the art of dancing on the edge of the abyss—they toast to freedom in whispers while bowing to the tsar in public.” “Our educated classes have developed an extraordinary talent: they can simultaneously read Voltaire and praise the censors who ban him.”

“Is a man less right merely because no one agrees with him? And how can universal insanity refute personal conviction?” “The masses are indifferent to personal liberty and freedom of expression; they enjoy authority. To govern themselves doesn’t enter their heads”—but “tyranny would not survive a month if people did not find ways to make it bearable through their small corruptions and pleasures.”

On Russian bureaucracy: “In Russia, there are two main powers: the autocratic power of the Tsar and the autocratic power of common sense. Unfortunately, they rarely coincide.” On European revolutionaries: “They take their wishes for reality, whereas the despots take reality for their wishes.”

Born to nobility in Moscow in 1812, Herzen was imprisoned several times and forced into European exile in 1847. His democratic ideas threatened the Tsar’s autocratic regime, and his work was banned—though it spread underground. London served as Herzen’s base for continued political activity and writing.

In his best-known work, From the Other Shore, and his memoir, My Past and Thoughts, he wrote of how revolutions become self-devouring and dreams of progress crash into realities of power. In France, he witnessed the 1848 revolution transformed into a dictatorship, which shaped his doubt about grand schemes—”ideological promises that, in practice, become new forms of domination.”

“It is time for us to stop dealing in abstractions, ready-made ideas, and a priori principles. Abstractions are the algebra of revolution, but algebra is not life.” Disillusioned with rigid ideological thinking, Herzen emphasized the contradiction in simultaneously dismantling the state while using state power to consolidate authority.

Herzen denounced public intellectuals who justified authoritarianism as moral guardianship against social dissolution, carousing in “timeless truths,” saddened by suffering along the way. For him, liberation demanded skepticism toward all absolute systems, whether state-enforcing or state-abolishing.

Today’s terminology for ideological conflicts—”cancel culture,” “wokeism,” and even “culture war”—often trivializes fundamentally serious questions: How does ideology reconcile with biological reality? Can addressing historical racism avoid creating new forms of discrimination? Is present injustice ever justified as compensation for past wrongs? These engage both liberals and conservatives, questions that Herzen would press with his combination of moral conviction and measured restraint.

Reflecting on historical progress and revolution, Herzen wrote, “We need wit and courage to make our way while our way is making us. History has no libretto. We do not need the past as a sanctuary or prison but as a lesson and, sometimes, as a warning.” Chief among warnings is the demotic guise of triumphalist leaders—authoritarians promoting respectable morality and invoking past glory as the promise of the future.

A conservatism truly new could proceed from causes that exist today and the self-questioning of tradition itself. With that, liberalism could become more conservative, getting off its own high horse and become more alluring—more lasting, this time, than the chic it, too, once enjoyed.

Notes and reading

Wilson Carey McWilliams – Political moral philosopher – Oberlin, Rutgers. Carey was a longtime mentor and close friend. He fervently introduced me to Herzen. I am grateful.

All Herzen quotations are from My Past and Thoughts (1870, 1982) and From the Other Shore (1855, 1979). Strong introductions by Isaiah Berlin, a foremost authority on Russian intellectual history.”

“Rediscovering Alexander Herzen” – William Grimes, The New York Times (February 5, 2007). – Herzen was critical of the Russian Orthodox Church’s close relationship with the tsarist autocracy and viewed organized religion as often being used to support oppression. He became an advocate for a secular humanism.

“We’re hotter now. . .” – Donald Trump. “Administration Hopefuls Descend on Mar-a-Lago” – Antonia Hitchens, The New Yorker (November 22, 2024).

The Cultural Ascendancy of the New Young Right – “The Cruel Kids’ Table: After conquering Washington, sights set on America,” Brock Colyar, New York Magazine (January 27, 2025).

Revolutionary chic – political fashion and “new forms of domination” – During the French Revolution (1789-1799), fashion became law under the Law of Suspects. Citizens displayed revolutionary allegiance through short hair, pantalons instead of aristocratic culottes, plain dresses, no more of those boned corsets, and no perfume. Though fashion evolved before the 1848 Revolution, it never returned to pre-revolutionary excesses. Anne Higonnet explores this phenomenon in her recent book Liberty, Equality, Fashion: The Women Who Styled the French Revolution (2024). Higonnet is an art historian at Barnard.

“Vanquished death with death” – Herzen – Matins, Easter Sunday, 1848. Chapter IV, “Vixerunt!” From the Other Shore. “An Open Letter,” September 1851:

“The future of Russia does not depend on herself alone: it is bound up with the future of Europe as a whole. Who can foretell what lies in store for the Slav world, should Reaction and Absolutism triumph over the European Revolution? Perhaps it will perish—who knows? But then Europe also will perish. . . . And history will continue in America.”

Tip-Off #188 – Rugged democracy

Tip-Off #187 – Kindred spirits

About 2 + 2 = 5