During her life, poet and essayist Adrienne Rich stood among America’s foremost public intellectuals. When she died in 2012, she had become one of the nation’s most respected poets, known for dealing with political issues in her poems while maintaining their artistic complexity and emotional depth.

Rich was well known for her political activism, radical feminism, and advocacy for lesbian rights and visibility. Her poetry inspired her politics, not the other way around. For Rich, this wasn’t simply about artistic responsibility but art’s nature—a timely lesson for tumultuous times. Several insights not from analyzing her poetry but understanding what it reveals:

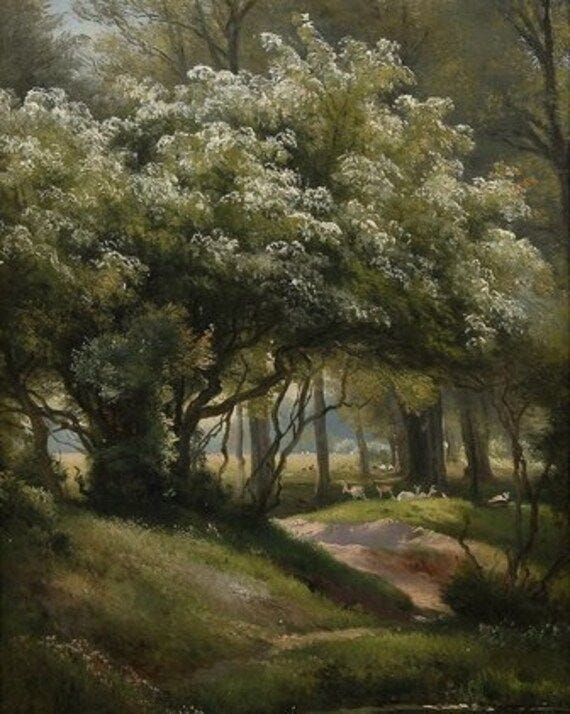

In her 1995 collection Dark Fields of the Republic, Rich’s opening poem “What Kind of Times Are These?” announces the collection’s theme and her recognition that directness may sometimes be impossible. The poem’s title comes from Bertolt Brecht, the revolutionary German playwright and poet. Rich provides Brecht’s lines in notes: “What kind of times are these / When it’s almost a crime to talk about trees / Because it means keeping still about so many evil deeds?”

In response to Brecht’s poem, Rich modifies his lines to imply that a poet must discuss trees to captivate readers in this era of apathy and cynicism. Where Brecht sees a form of complicity with evil, Rich transforms the metaphor, suggesting that in modern America, engaging with natural imagery may be the only way to make readers receptive to difficult political truths—not as strategy but discovery of what is already there, neglected. The trees themselves convey meaning about power, persecution, and resistance. “These are the things we have learned to see who live in troubled regions.”

Rich resisted the slogan “the personal is political,” seeing in it not liberation but reduction—a diminishing of personal experience, including poetry, to mere politics. Instead, she believed politics and public life should be enriched and expanded by personal experience and poetic truth. We artificially divide our single, unified life—as futile as separating breath from air or our private existence from the public world that sustains it. Even desert monastics, in their apparent solitude, remained bound to the larger community of the Church.

Our word “idiot” comes from the Greek word idiotes, which originally meant someone who refused to participate in public affairs; a purely private person was, by definition, ignorant. The Greek understanding was not about the importance of being relevant—today’s virtue—but about doing justice to who we already are. For Aristotle, we are political animals: creatures who live, think, grow, choose, and decide in relationships with others. Just as the forest defines a tree’s nature, the human community and nature define our political character. We are each other’s destiny.

Poetry helps us reimagine the world. From our “suburbs of acquiescence,” Rich urges us to question reality and find beauty in darkness without succumbing to it. The true divide lies not between secular and sacred, natural and supernatural, but between those who grasp language’s metaphoric power and those who reduce it to formula. When language grows formulaic, it becomes a weapon of repression, wielding empty certitudes to enforce obedience and truth as partisan clickbait.

Rich all but declares that we inhabit a flat-earth society. Imagination is a commodity, and everywhere, the same. Moscow is Washington, and a gift shop in Antarctica sells Trump T-shirts. Politics is a “rabbit hole,” an endless dead end. This cliché is upended by a poetic sensibility, which restores Lewis Carroll’s original vision: Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole leads not to entrapment but to a world of fantastical possibilities. What seems a dead end becomes a gateway to self-discovery, where strange encounters and nonsense demand adaptation and yield unexpected insights. Fantasy is preparation for a crazy world. We have to learn to draw straight with a crooked line.

At the height of the Vietnam War, acclaimed author Frederick Buechner was working on his cryptic novel about a 12th-century holy man attempting to overcome pride in his humility. “When I should be doing something real, I’m writing about a monk’s pride.” His friend, the prominent anti-war activist Yale chaplain William Coffin, replied, “Sit on your ass and keep writing!”

Adrienne Rich would have applauded. The social justice warrior was, first and foremost, a poet. She knew something a good poet believes: The world’s in a mess; hit the streets when duty calls. But never forget to “sit on your ass and keep writing.” Excellence is part of the fight for justice.

Sometimes sentimental, she could have added, “The world needs you the way you are. Get better.”

Notes and reading

“There is a haste to dismiss art that doesn’t yield immediate political results—a discomfort that has haunted both Left and Right, as it haunted Plato. While I knew poetry could unlock new possibilities and restore feeling, I had internalized that peculiarly American notion that poetry is powerless to shape society. I do not accept this idea. Yet it has haunted me.” – See Adrienne Rich, What Is Found There: Notebooks on Poetry and Politics (Expanded Edition, 2003), “Preface” and “Jacob and the Angel.”

Collected Early Poems: 1950–1970.

Dark Fields of the Republic, Poems 1991–1995.

“Storm Warnings” – in Rich’s first published poetry collection, A Change of World: Poems (1951), forward by W.H. Auden.

Outward: Adrienne Rich’s Expanding Solitudes – Ed Pavlić (2021). Drawing on their relationship, Pavlić covers the arc of Rich’s career and shows how she depicts our lives—from the public to the intimate—in shared space rather than “owned privacy.” Pavlić is Distinguished Research Professor of English, African American Studies, and Creative Writing at the University of Georgia.

. . . draw straight with a crooked line. – variously attributed.

Buechner-Coffin exchange – from personal conversation.

> Polarization reflects not merely a “failure to communicate” but linguistic ignorance.

What is lost when language dies? Was Babel a blessing? – Veronica Esposito, World Literature Today (March/April 2025), “Language as Refuge.” – Esposito is a family therapist who was a judge for the 2022 National Book Award in Translation. She is a regular contributor to respected venues.

Cf. Adrienne Rich, The Dream of a Common Language: Poems 1974–1977.

> Inhabiting ambiguity – “We are masters of ambiguity. We habitually offer words and actions which are not univocal, but compatible with a number of interpretations and which snap into a shared grid that is being tacitly and continuously negotiated.” – Judith Wolfe, The Theological Imagination: Perception and Interpretation in Life, Art, and Faith (2024). Chapter 3. – Wolfe is Professor of Philosophical Theology at the University of St. Andrews.

> Cf. The “fascism” of ambiguity: Conceptual precision through poetry and music. – Vagueness and unclear meaning can become their own form of tyranny. When truth is made to seem permanently uncertain, resistance is questionable.

Tip-Off #180 – Time out

A Brief for the Defense

About 2 + 2 = 5